Hateful Memes Challenge

Yuval Nirkin Assaf Rabinowitz Yoni Solel

Overview and Motivation

Over the past years, memes (captioned photos intended to elicit humor and other emotions) have been widely common all around the internet and especially in social networks.

Memes have been shown to serve many purposes, such as entertainment and marketing. However, the wide usage of memes does have a negative side to it, as there are memes that combine certain texts and photos in ways that are being used to hurt a person's or group's feelings, we will refer to those as "Hateful Memes" (HMs).

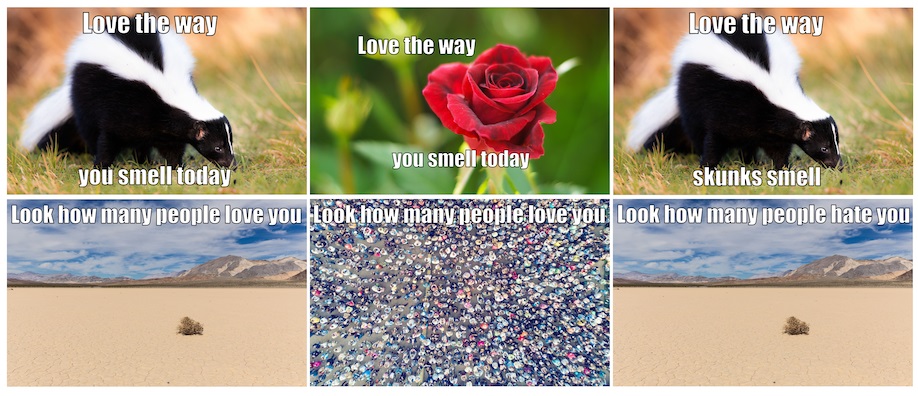

Memes examples. The examples illustrate that while the combination of text and image may be hateful, in many cases both the text and the image are not considered hateful on their own. Top row: meme A1 is hateful while memes A2, A3 are not. Bottom row: B1 is hateful while B2, B3 are not.

Since those HMs could potentially be harmful as they may be used for cyberbullying and incitement, it would be very beneficial to be able to identify a HM on social networks, thus enabling us to block or report the HM. However, at the massive scale of the internet, the task of detecting multimodal hate is both extremely important and particularly difficult.

We will take part in a competition by Facebook that aims to classify memes into hateful and non-hateful memes.

We will first use various methods from the fields of data analysis and deep learning to analyze the given dataset (described below) and extract new features. Following, we will construct a classification model based on image and text processing that aims to detect HMs.

Problem statement

Our goal is to predict whether a meme is hateful or non-hateful. This is a binary classification problem with multimodal input data consisting of the meme image itself (the image mode) and a string representing the text in the meme image (the text mode).

Given a meme image file, and a string representing the text in the meme image, our trained model should output the probability that the meme is hateful, where a meme would be classified as hateful if this probability is larger than 0.5.

Dataset

We will use a dataset made by facebook specifically for that purpose.

The features in this data set are the meme images themselves and string representations of the text in the image. The meme images and text extractions live in separate files, they can be matched to each other using the meme id.

The directory is called img and it contains all of the meme images to which we'll have access: train, dev, and test. The images are named <id>.png, where <id> is a unique 5 digit number.

The three files are JSON lines, or, .jsonl files.

- train.jsonl

- dev.jsonl

- test.jsonl

Each line in a .jsonl file is valid JSON. In our case, each line of JSON corresponds to one and only one meme in the img directory. A meme referenced in train.jsonl belongs to the training set, whereas dev.jsonl memes are intended to be used for model validation, and test.jsonl memes will be used to generate your submissions to the competition leaderboard.

All .jsonl files provide the following fields

- Id. The unique identifier between the img directory and the .jsonl files, e.g., "id": 13894.

- Img. The actual meme filename, e.g., "img": img/13894.png, note that the filename contains the img directory described above, and that the filename stem is the id.

- Text. The raw text string embedded in the meme image

Additionally, if the meme belongs to train.jsonl or dev.json, it will contain the additional field giving the label

- Label. where 1 -> "hateful" and 0 -> "non-hateful"

Of course, there are no provided labels for the memes referenced in test.jsonl.

Related Work

Language processing

As described in the previous section, our input consists of (i) text and (ii) image. The main method that we used in order to preprocess the text is called "text embedding". Text embedding and its implementations will be the highlight of this section. We will discuss some common implementations and show results of a simple model trained exclusively on the output of these implementations.

Shortly, text embedding is the process of transforming given text to a numerical representation that later may be feeded into a model. The idea is that many ML models require the input to be represented as a fixed-length feature vector. On the other hand, in order to classify according to these vectors, we need them to capture the semantic, syntactic context of the given text in order to understand how similar/dissimilar it is to other texts.

One of the most common fixed-length features is bag-of-words (BOW). This method has 2 steps:

- Design the Vocabulary - list the relevant words to our classification. Assume our vocabulary holds n words.

- Create Document Vectors - Count how many instances of each vocabulary word appear in the given text. The output is a vector of size n.

This method is very simple and flexible, and can be used in a myriad of ways for extracting features from documents. However, it suffers from two major weaknesses: they lose the ordering of the words and they also ignore semantics of the words. For example, the words "Paris", "powerful" and "strong" are equally distant. We would prefer a representation in which "powerful" and "strong" will be closer than "powerful" and "Paris".

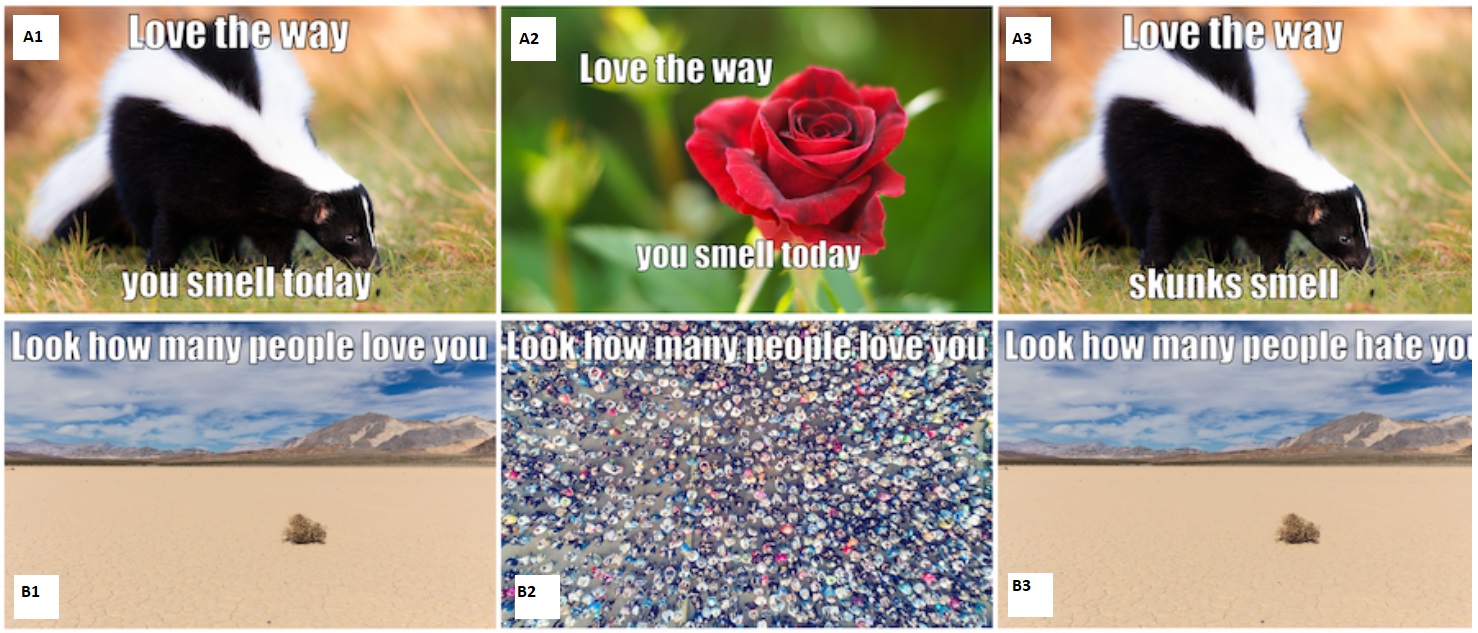

The Word2Vec , presented in 2013 [1], intends to give you just that: a numeric representation for each word, that will be able to capture such relations as above.

Word2Vec representation is created using 2 algorithms: Continuous Bag-of-Words model (CBOW) and the Skip-Gram model. We used the CBOW model. In this model, we creates a sliding window around the current word, in order to predict it from its "context" — the surrounding words. Then, each word is represented as a feature vector. After training, these vectors become the word vectors.

The problem with this method is that documents, unlike words, do not come in logical structures such as words. As a result, one of the authors of Word2Vec, Tomas Mikolov, introduced in 2014 [2], an improved approach called Doc2Vec. This approach, heavily based on Word2Vec, intends to embed a complete document using a small modification on CBOW. In addition to the surrounding words, the training phase is given a unique ID per document in order to give document-based context to the training. In the end of the training, the document-vector holds a numeric representation of the document.

In 2018, Google AI published a new, state-of-the-art approach called BERT [3]. According to them, the problem with all of the above methods is they are "context-free":

"For example, the word "bank" would have the same context-free representation in "bank account" and "bank of the river." Contextual models instead generate a representation of each word that is based on the other words in the sentence. For example, in the sentence "I accessed the bank account," a unidirectional contextual model would represent "bank" based on "I accessed the" but not "account." However, BERT represents "bank" using both its previous and next context — "I accessed the … account" — starting from the very bottom of a deep neural network, making it deeply bidirectional".

In our model, we preproccessed our text using SBERT, which was published in 2019 [4]. SBERT is a modification of the pretrained BERT network that uses siamese and triplet network structures to derive semantically meaningful sentence embeddings.

Efficient image classifiers

Efficient neural networks are attracting significant research attention due to their high accuracy to efficiency ratio which enables many mobile applications. MobileNetV1 [5] introduced the depth-wise separable convolution which reduced the number of parameters and FLOPs of regular 3x3 convolutions without minimal impact on accuracy. MobileNetV2 [6] suggested the inverted residual block that wraps the depth-wise separable convolution with an initial linear expansion layer and ending with a linear projection layer. This block helped improve performance farther. Recently, MobileNetV3 [7] optimized the previous architecture using hardware-aware neural architecture search together with a squeeze and excite component that is added to the inverted residual block.

Hypernetworks

A Hypernetwork [8] is a network that predicts the weight of another, usually larger, network. The hypernetworks were first suggested as a way to perform dynamic weight sharing between networks and now they are becoming increasingly popular due to their success as an implicit function for 3D scene representation [9] and Neural architecture search (NAS) [10].

Exploratory Data Analysis

Since our dataset is inherently divided into two parts:

- images dataset

- text dataset

we will attempt to extract feature independently for each part:

- Image dataset features:

- Mean value for each RGB coordinate in the picture

- Standard deviation for each RGB coordinate in the picture

- Image width

- Image height

- Image width to height ratio

- Image caption:

- Image caption is a text with one or more sentences describing the image.

- The Image captioning was performed using deep learning method combining two neural networks:

- CNN – used to compress the input images

- LSTM – used to generate a sentence out of the compressed image

The combined network will be trained using COCO dataset.

- Caption profanity probability:

- Using "profanity" library

- Text dataset features:

- Words contained in the sentence

- Number of words in the sentence

- Number of subparts in the text

- Text profanity probability

- Using "profanity" library

The full EDA can be found in the relevant GitHub folder.

From analyzing the described features we can see a few features that can seemingly provide an indication of the meme being hateful:

*In all the following graphs red symbolizes the non-hateful memes and blue symbolizes the hateful ones.

- Width :

We can see that the hateful memes are more likely to be of bigger width than the non-hateful ones

- Height :

We can see that the non -hateful memes are more likely to be of smaller height while the non-hateful ones height is relatively balanced

- Text profanity :

The graph suggests that a hateful meme text is more likely to contain profanity.

Since an image can be cropped or resized, it is reasonable to assume that the height and width will not provide a good indicator for the meme being hateful. However, the image dimensions along with the mean and std of each RGB coordinate do provide valuable information for the final classifier construction. On the other hand, the text profanity feature might be a good indicator for hateful-memes as we will show.

*Notice that unlike the text profanity, the caption profanity feature does not provide a good indicator for the meme being hateful. This could be explained by the nature of the images and by the non-profanity vocabulary from which the caption is built.

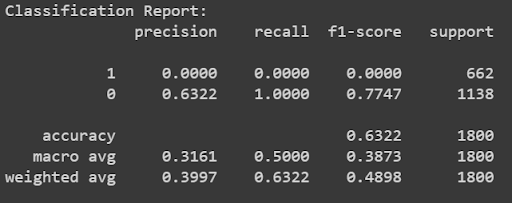

In order to roughly assess the quality of extracted features we will make two separate simple classifiers using those features:

-

Logistic regression classifier:

- Using logistic regression we got the following :

-

From the model coefficients we can deduce that the most dominant feature is, as we expected, is the text profanity feature.

-

SVM classifier:

- Using SVM we got the following:

Overall we can deduce that from the various features we extracted, the most prominent one seems to be the text profanity feature, however using those features alone with simple models such as LR or SVM does not seem to provide a sufficient solution.

Method Description

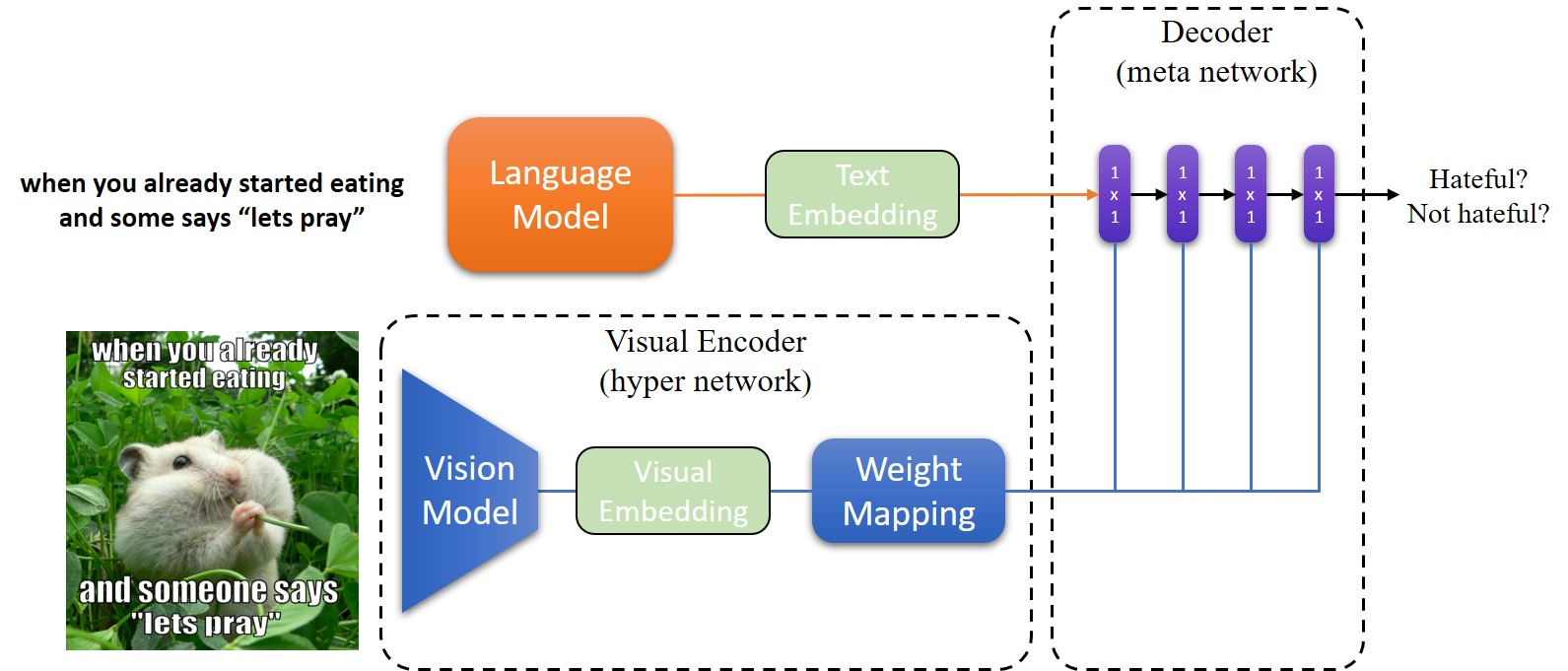

The hateful memes challenge requires combining two very different domains: text and images. The first is of a sequential structure while the latter is spatial. Taking this into consideration together with our limited training hardware options we opted for an efficient solution, and therefore we decided to base our method on the hypernetwork [8]. The hypernetwork is a network that predicts the weights of another larger network, allowing us to bridge our two different domains without explicitly combining their embeddings which can make the model unnecessarily large. Our method overview is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 7: Our method pipeline. Upper left: the language model which produces the text embedding. Bottom left: the visual encoder containing the visual model and a weight mapping model. Right: the decoder that produces the final prediction.

As can be seen in the figure, our model consists of three main components: the language encoder, the visual encoder, and the decoder. The language model is based on SBert, it accepts the image's text and produces the text embedding \(E_t\). The vision model accepts the image as input and produces the visual embedding \(E_v\), which is then fed to the weight mapping module, producing a set of weights \(\theta\). The decoder is defined as a function \(f(E_t,\theta)\), accepting the text embedding \(E_t\) and the weights \(\theta\), that outputs the final binary prediction, is the image hateful or not hateful?

Vision Model

Our vision model is based on the Mobilenet V2 [6] architecture, as it is both fast and memory efficient and is well suited for limited hardware. Given an input image $I\in\mathbb{R}^{3\times800\times800}$ the vision model outputs an embedding vector \(E_v \in \mathbb{R}^{768}\) which is then fed to the weight mapping module.

Weight Mapping

The weight mapping module receives an embedding vector as input and outputs a set of weights matrices \(W_1,W_2,\dots,W_n\) corresponding to the n linear layers in the decoder. The weight mapping module consists of multiple linear layers each receiving a part of the input vector that is directly related to the number of parameters required by the specific decoder layer, the more parameters the larger the relative part of the input vector that will be received.

Decoder

The decoder is a meta network built as a multilayer perceptron (MLP), it receives its weights from the visual encoder, allowing it to be specialized for each input image. Each linear layer is followed by a batch normalization layer and a ReLU activation layer. Given a text embedding from the language model, the decoder outputs a binary prediction, hateful or not hateful.

Training

We train our model end-to-end, with the vision model pretrained on ImageNet [11], and the weight mapping module is initialized by random values drawn from the normal distribution. The language model is pretrained on Wikipedia [12] and its weights remain frozen for the entire training process. We train our model using the Adam optimizer (\(\beta_1=0.5,\beta_2=0.999\)) with learning rate 0.0001 which we decrease by half every five epochs, and a batch size of 4. All images are resized and padded to a resolution of 800x800, and randomly horizontally flipped with probability 0.5.

Results

Text-Embedding Based Model

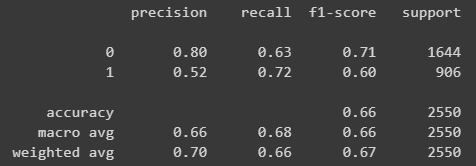

We would like to evaluate the performance of 2 of the above methods. In order to do so, we embedded the texts and fed them into a simple model and examined the results.

Our model consisted of an input layer, with the size of the embedding, one hidden layer with the same size and an output layer of 1 node followed by a sigmoid function (in order to output valid probability values).

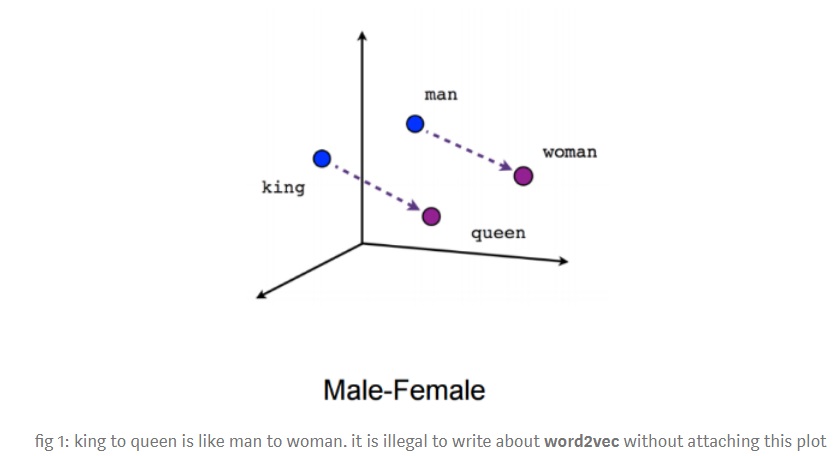

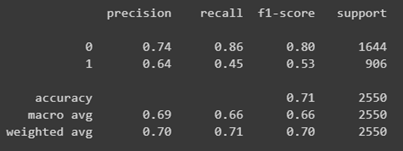

We examined the results of Doc2Vec and SBERT. Both methods are exposed by a user-friendly python API:

Doc2Vec Results - 0.63 Accuracy

SBERT Results - 0.71 Accuracy

We can see from the results that SBERT outperforms Doc2Vec. According to these results, we decided to use SBERT as our text-embedder. Following is additional evaluation of SBERT:

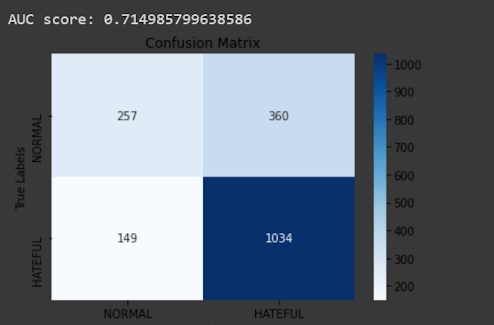

SBERT - AUC & Confusion Matrix

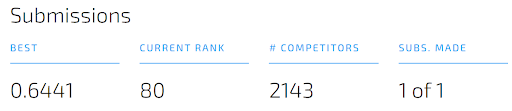

At this point we submitted this simple model (remember - we have not used information from the images at all):

Our first submission

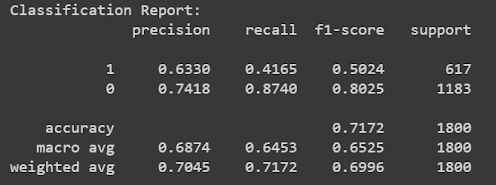

Complete Model

Using our complete model as described in the previous section we were able to achieve an AUC score of 0.6707.

At the time of writing we were ranked 113 out of 2765 competitors.

Conclusions and future work

Most of the images in the dataset are very large yet only a small amount of pixels actually contain relevant information (e.g. small objects of interest), this makes it difficult to extract meaningful context as can be seen by the rather small improvement of our full model relative to using only a language model. An interesting direction can be to utilize an attention mechanism to allow the network to only focus on the important parts of the image rather than a single global embedding that is averaged and pooled from the last feature map.

Usually the text in meme images is located in the background regions of the images which do not contain any important information. Avoiding the processing of the text regions can help focus the network on the important parts of the images and increase the efficiency of the network. Finding the text regions can be done using simple OCR as the text is always aligned horizontally.

References

[1] Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G. and Dean, J. (2013). Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. [online] arXiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1301.3781.

[2] Le, Q.V. and Mikolov, T. (2014). Distributed Representations of Sentences and Documents. [online] arXiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1405.4053.

[3] Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. and Toutanova, K. (2018). BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. [online] arXiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805.

[4] Reimers, N. and Gurevych, I. (2019). Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. [online] arXiv.org. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.10084.

[5] Howard, A.G., Zhu, M., Chen, B., Kalenichenko, D., Wang, W., Weyand, T., Andreetto, M. and Adam, H., 2017. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.04861.

[6] Sandler, M., Howard, A., Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A. and Chen, L.C., 2018. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 4510-4520).

[7] Howard, A., Sandler, M., Chu, G., Chen, L.C., Chen, B., Tan, M., Wang, W., Zhu, Y., Pang, R., Vasudevan, V. and Le, Q.V., 2019. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 1314-1324).

[8] Ha, D., Dai, A. and Le, Q.V., 2016. Hypernetworks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.09106.

[9] Sitzmann, V., Martel, J.N., Bergman, A.W., Lindell, D.B. and Wetzstein, G., 2020. Implicit neural representations with periodic activation functions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.09661.

[10] Zhang, C., Ren, M. and Urtasun, R., 2018. Graph hypernetworks for neural architecture search. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.05749.

[11] Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L.J., Li, K. and Fei-Fei, L., 2009, June. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 248-255). Ieee.

[12] Dor, L.E., Mass, Y., Halfon, A., Venezian, E., Shnayderman, I., Aharonov, R. and Slonim, N., 2018, July. Learning thematic similarity metric from article sections using triplet networks. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers) (pp. 49-54).